Quick Assist is Microsoft’s native remote access solution for tunneling a desktop connection across the internet. It enables a user to troubleshoot printer issues for family members from the comfort of their home.

It’s also potentially of great value to attackers. And it ain’t exactly easy to monitor or investigate.

How does it work?

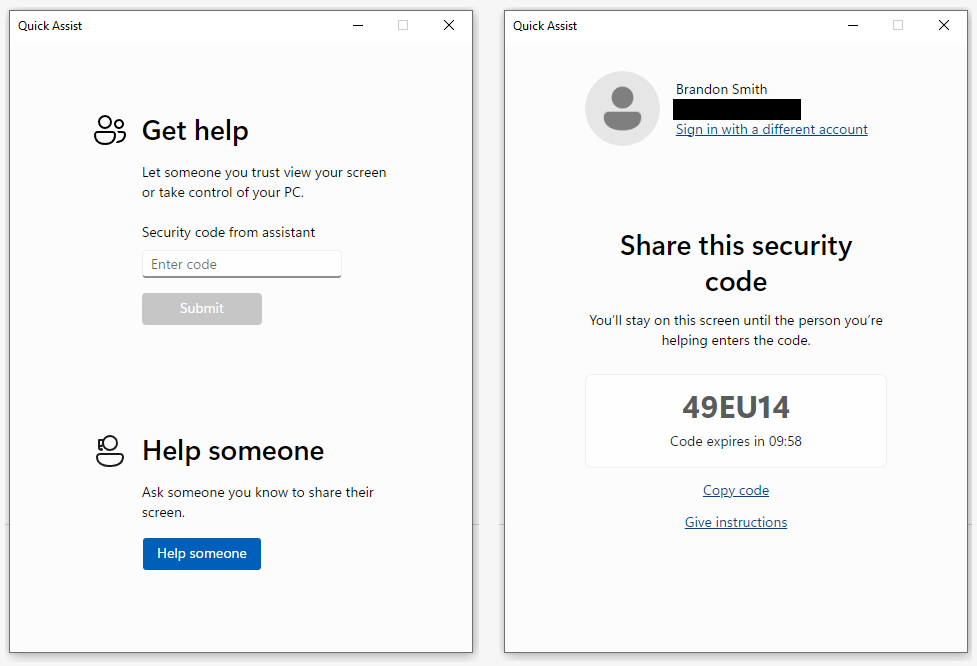

Quick Assist is enabled by default on all standard Windows deployments. Feel free to read that again. To use it, the remote party (client for our purposes– the one who will be viewing/controlling the other device) opens quickassist.exe from her device. She clicks “Help someone,” logs in with an arbitrary Microsoft account, and is given a 6-character code to provide to the target. This target (server here– the one whose device will be viewed/controlled) enters the 6-character code, clicks allow, and the screen is shared. From there, the client can request full control of the device.

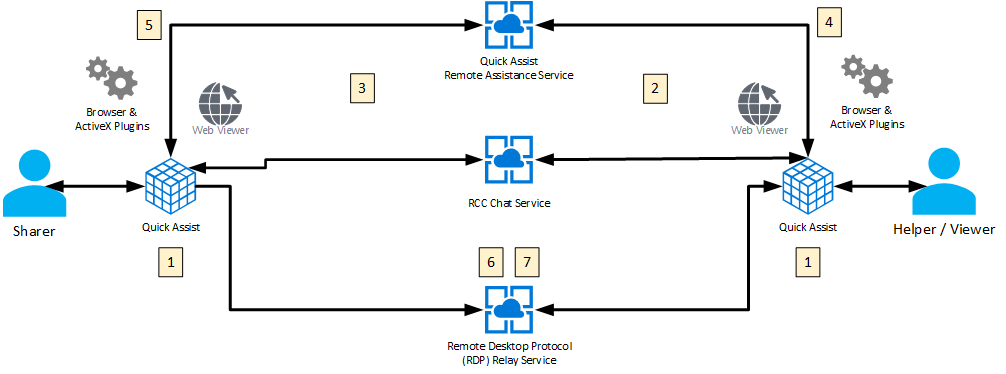

The TL;DR on Quick Assist is that it uses HTTPS over Microsoft domains to establish an RDP session between hosts. It’s described in better detail by Microsoft.

External threat scenario

Consider two social engineering scenarios:

Scenario 1: A stranger claiming to be with your help desk rings your user and tells her that there’s a security issue with her device. To fix it, the stranger asks your user to download ultraviewer.exe, then read off the newly generated ID and password before clicking to allow access.

In this case, I think we can hope that our user is wise enough for this to appear suspicious. She’s being asked to download something from an external domain (which our AV engine gets a crack at), then give the adversary whatever she needs to begin a session.

Scenario 2: A stranger– also claiming to be from IT– rings your user and gives the same line about a security issue. But this time, our stranger claims that the user won’t need to download anything, because IT has already placed the requisite program on her device. Instead, all she has to do is press Windows+CTRL+Q. From there, our stranger reads off a six digit code to be entered by the user, and a session is underway.

With this second scenario, the attacker has undermined quite a few elements that could cause suspicion, and has a shot at gaining access to the device using what amounts to a LOLBAS RAT. She can pop open a Powershell window, download cradle a second stage, and be off to the races.

If you’re social engineering for access with any other tool, why?

Challenges for Monitoring, Detecting, and Investigating

Quick Assist presents a slew of problems for those who have a need to keep an eye on it.

First of all, it’s hard spot a connection in network logs. When quickassist.exe is launched, it immediately loads multiple msedgewebview2 processes and resolves remoteassistance.support.services.microsoft.com to load the landing screen shown above. So not every Quick Assist launch– or even every DNS request by Quick Assist– is indicative of a sharing session. Plus, session creation does not involve the creation of any new child processes, or even additional module loads. Even the call to the Win32 screenshot API is performed on initial launch. As with a normal RDP session, process launches in a remote control session aren’t attributed to quickassist.exe.

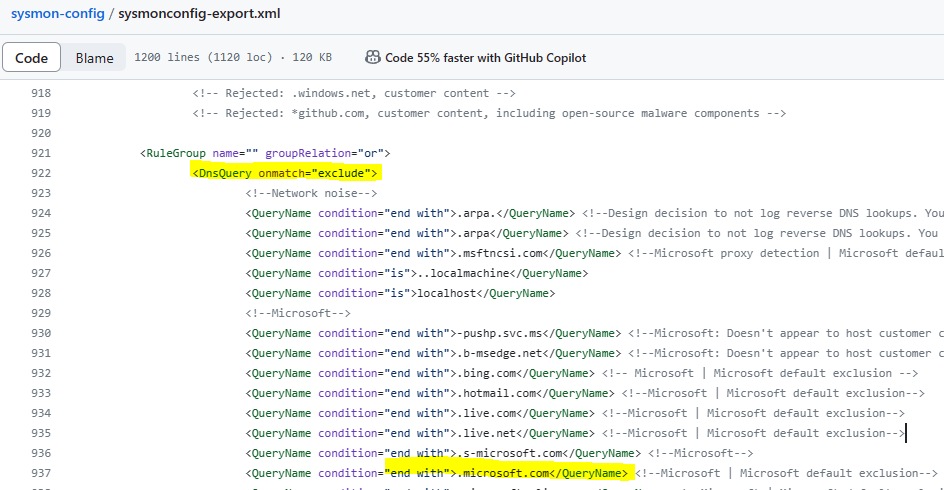

You’re also probably not even logging the DNS activity associated with a connection at the host level. The widely-used SwiftOnSecurity configuration for Sysmon saves on storage by suppressing logging for some extremely well-traveled domains, among which is every subdomain of microsoft.com. This means that the entire infrastructure used for session establishment is suppressed.

If asked to pick something that would not create event logs, this would not have been my choice. But there’s no event log created by this tool to reflect any stage of session establishment, remote control, or session termination. Application/services logs do contain a Remote Assistance/Operational evtx events, but these seem to be related to components of the legacy Remote Assistance tool. Events there that pertain to Remote Assistance COM server do not correspond with Quick Assist usage.

Finally, a network layer block to lock down usage of this tool isn’t straightforward. It’s all in Microsoft IP space. Moreover, the DNS requests used to set up a session return a series of CNAME records before finally resolving an IP. That means outside of sinkholing specific requests, a host-side control is the best option.

The DFIR of it all

Detecting Usage

We’ve still got a couple of opportunities to detect remote sharing or control activity, through both networking and log data.

From a DNS perspective, the operative moment occurs at step 5 of the diagram above. When a host connects to the Microsoft RDP relay service on port 443, it issues a DNS request for a region-specific domain matching the pattern rdprelayv3*.support.services.microsoft.com (e.g. rdprelayv3eastusprod-4.support.services.microsoft.com). This occurs regardless of whether the host is entering the session as the client or the server, but is high-fidelity confirmation that at a minimum, a screen share session has occurred.

Absent network-wide DNS logs, this is captured beautifully in Microsoft Defender for Endpoints:

DeviceNetworkEvents | where RemoteUrl contains "rdprelayv*" and InitiatingProcessCommandLine contains "quickassist"

If you have certain policies enabled in Windows Advanced Audit Policy Configuration, you’re in an even better position. Windows logs certain Ncrypt/DPAPI events in Security logs and an event code 5058 is generated when an operation is performed on a file containing a key by using a Windows key storage provider. For our purposes, such an event occurs at the start of any successful connection. These events can be identified with the following:

index = [Windows Event Logs] EventCode=5058 ProcessName="*quickassist.exe" KeyName="Desktop Sharing"

Note that these events are only logged on the server side – the side being viewed/controlled– making them particularly useful as an indicator of which side our subject host was on. A series of related events are logged at the beginning of a session, but in many cases it can be fruitful to use the ProcessID from these events to correlate with Sysmon 5 or Security 4689 events in order to temporally bracket the session.

Forensic Review

Despite the lack of native logging, Quick Assist presents a solid quantity of forensic material to work with.

Naturally, the SRUM database (C:\System32\sru\SRUDB.dat) will provide useful context for connections in the last 60ish days. When parsed (with a tool like SrumECmd.exe), .csv rows for quickassist.exe will show the volume of network traffic in and out via the tool. If volume of data out > volume of data in, we can safely conclude that the forensic subject was the server, sharing their screen and potentially granting remote access. If volume of data out < volume of data in, then the subject was acting as the client in a remote connection.

The overall volume of data can also be telling. While the server does stream its screen live, it does so with native Windows RDP efficiencies. In some testing, I found that my host (in a server role) streamed a little over 25 MB of data in about 10 minutes of low-activity session.

And speaking of those RDP efficiencies, also look for evidence in the subject’s RDP bitmap cache (C:\Users<User>\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Terminal Server Client\Cache). Because a screenshare session through Quick Assist is a real life RDP connection, a bitmap cache binary file is created on the client host, with a modification time that matches the cessation of the last session. An absence of such a cache file suggests that the subject was on the server side of the connection (note, however, that the cache can be cleared by the user trivially). Bonus: parse the cache with a utility like bmc-tools.py for a jigsaw puzzle that will give you a sense of what she was looking at.

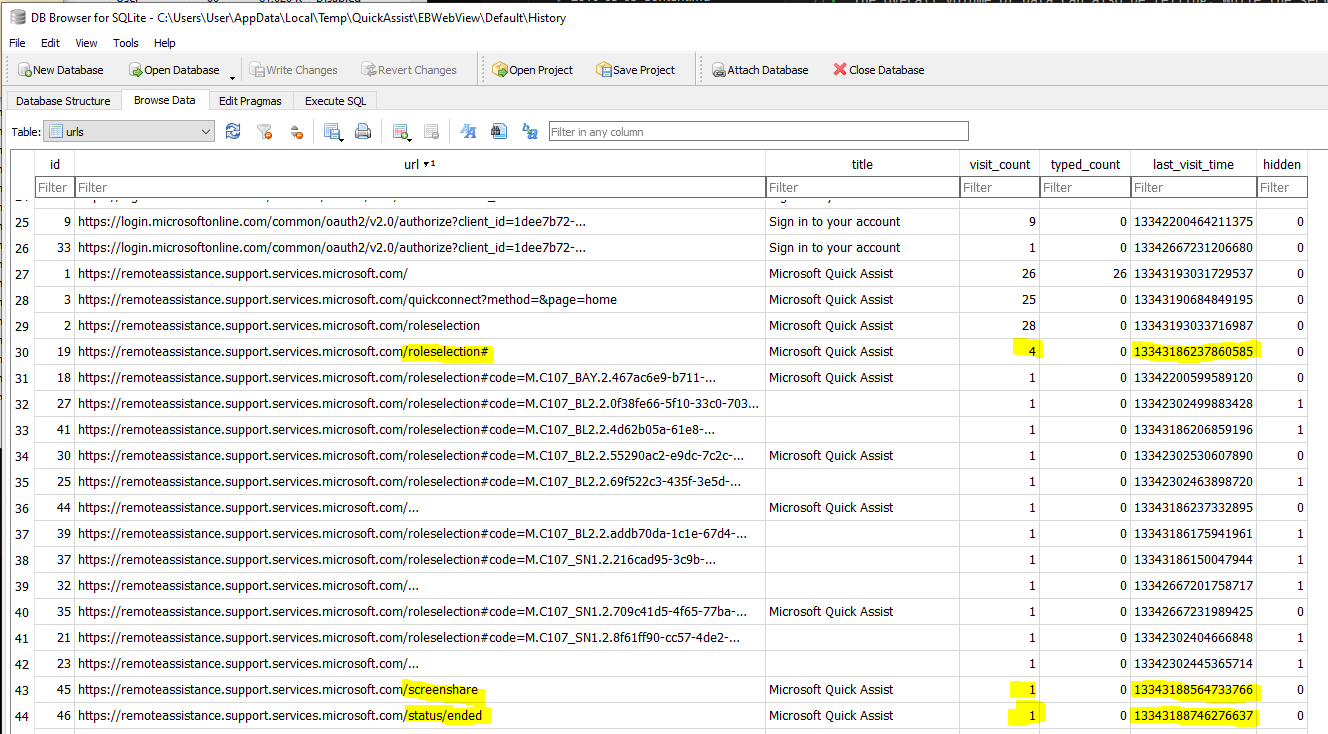

Next, Quick Assist is kind enough to produce some artifacts in the AppData/Temp directory that are quite useful, and that it does not clean up expeditiously (I have found no sign that the application deletes them at all). The most significant is a series of SQLite databases housed at %LOCALAPPDATA%\Temp\QuickAssist\EBWebView\Default. These artifacts closely mimic those created by Chromium-based browsers, thanks to the tool’s usage of msedgewebview2.exe While several databases are encrypted with string protected through DPAPI (the subject of a future post), the most important artifact is the database at %LOCALAPPDATA%\Temp\QuickAssist\EBWebView\Default\history. This database is unencrypted, and used to track historic sessions. Any SQLite browser can be used to view the “urls” table in the file. This table contains web hits by the tool during session negotiation and activity, including URLs, hit counts, and most-recent timestamps.

The row for https://remoteassistance.support.services.microsoft.com/screenshare is a means to track how many sessions the host has been part of. Its timestamp (expressed in Windows NT time format) shows the time the most recent session was joined.

The entry for https://remoteassistance.support.services.microsoft.com/status/ended reflects the end of a session. Its count will match the above, but its timestamp will show the end of the most recent session, allowing for accurate time bracketing.

A particularly useful value is at https://remoteassistance.support.services.microsoft.com/roleselection# (distinct from /roleselection with no #, and also distinct from /roleselection#argument1234567890…). The visit count for this row was observed to increment on the server host only during sessions when the client was given control via the Quick Assist session. Its timestamp reflects the most recent time when a remote entity was given control during a session.

Other files are created in the same subdirectory of the user’s AppData folder, and their timestamps reveal further information.

A large number of subdirectories and files within the corresponding Quick Assist folder are not created until the application’s first session. The %LOCALAPPDATA%\Temp\QuickAssist\EBWebView\Default\Secure Preferences database is not created upon launch of quickassist.exe, but its creation date reflects the instantiation of the first session joined by the host.

“%LOCALAPPDATA%\Temp\QuickAssist\EBWebView\Default\Network Action Predictor” changes upon session establishment, so its Date Modified represents the beginning of the most recent screenshare session.

“%LOCALAPPDATA%\Temp\QuickAssist\EBWebView\Default\Network\DIPS” is updated on session state change (i.e. session started, control granted, control relinquished, session closed). This means that its Date Modified represents the END of the most recent screenshare session.

And quite notably, a .txt file (e.g. 000003.txt) is created within “%LOCALAPPDATA%\Temp\QuickAssist\EBWebView\Default\Session Storage”. It contains the remoteassistance (truncated) domain resolved during session establishment, but more importantly, a list of session establishment dates/times in human-readable format.

Taken together, these artifacts present a useful volume of information that can be taken as the starting point for further analysis.

In a future blog post, I’ll do some further digging into accessing other, encrypted databases, and how to better discern directionality of connections.

UPDATE: After confirming that databases can be decrypted via a script to retrieve keys through the DPAPI, I found nothing of substantial, incremental value in these databases. The SRUM DB continues to be the most reliable way to ascertain directionality.